As always, feel free to unsubscribe if you don’t find this useful. If it is at least interesting, please consider checking out MattBall.org

TY & be well.

With everything going on in the world (including the ever-growing horrors of factory farming) yet another “smart” person used his mainstream platform to argue that insects feel pain. Here are three related pieces: the last, the most important bit and one of the most popular posts I’ve ever published, isn’t by me.

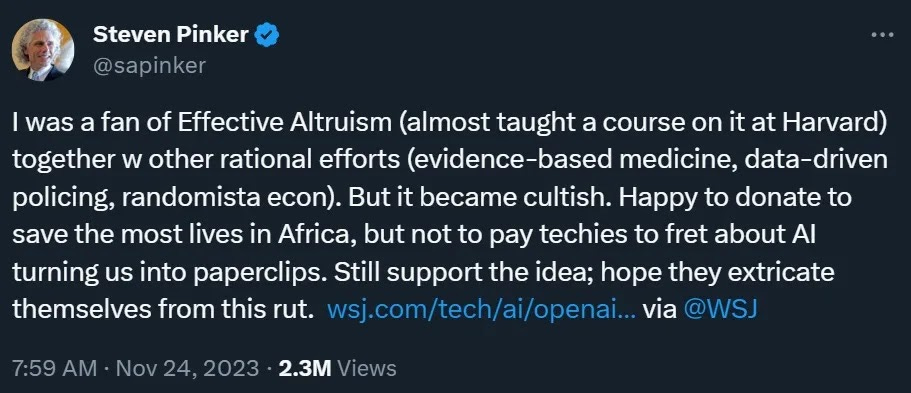

Self-Sabotage or Infiltrators?

Humankind isn’t just some abstraction. To love humanity, you must start by loving individual persons, by fulfilling your responsibility to those you love.

-Death's End

Once upon a time, some animal exploiter tried to convince an unstable person to plan a (thwarted) terrorist attack to make animal advocates look bad.

This comes to mind whenever I see people supposedly concerned with making the world a better place doing things beyond absurd. I wonder: are they infiltrators trying to discredit actual dedicated advocates? Or are they simply unhinged people without any connection to reality?

In this case, the person is unhinged - don't wash to save mites that live on you. OK, fine, the "Effective" Altruism community wants to allow weird brainstorming, even about non-sentient "wild" animals.

But whoever compiles the "best of" EA posts for the weekly newsletter actively chose to highlight and promote this insanity.

Ours is a world where countless fully-conscious human beings are actually and acutely suffering - including many individuals who are being tortured. Parents losing their five-year-old after a years-long battle with childhood leukemia. A teenager paralyzed by crushing anxiety. A new mother killed by a drunk driver, leaving behind a howlingly-despairing husband and infant. A political prisoner driven mad in solitary confinement.

And yet, in this world, the Effective Altruism community chooses to promote concern for non-sentient invisible mites that literally feed on us.

Ed Yong on Insects

tl;dr: Being able to sense things that are harmful – nociception – developed early in animal evolution. Only much later, when animals became long-lived and limited in reproduction, did the extra, very expensive neural hardware evolve to allow for the conscious, subjective experience of suffering. That allowed those long-lived animals to learn in a way that assists them later in their long life.

Our "pain" relieving medicines mostly work on our system of nociception, not our mental processes that turn those signals into pain (opioids might be an exception). So our "pain" medicines will work on other animals' nociception pathways, too, regardless of whether they actually experience subjective pain.

If this isn't enough to break the idea that "pain" and morally-relevant suffering are the same, please see this much deeper explanation, the most honest, good-faith deep exploration out there (even though I disagree with Luke).

This is important for several reasons.

The first is that many empathetic people (including many vegans) are inclined to equate "pain" with "suffering" and see "suffering" everywhere. I know a vegan who heard of a robot "escaping" and felt a twinge of moral sympathy for the robot.

Indeed, many vegans spend more time trying to "prove" that bees are being exploited by the honey industry than they do actually trying to effectively decrease factory farming.

And, of course, some EAs harp on insects in an attempt to "one up" everyone else's expected value.

Both groups are filled with people utterly invested in their position and who will angrily shout down / bombard anyone who has doubts with endless rants. It is like facing people who only watch Fox News.

This is not only a huge waste of time and energy, it makes vegans and EAs look nuts. (Sorry to be blunt, but both vegans and EAs have image problems. It isn't enough to be "right." What matters is being effective, and that involves concern for appearances.)

In addition to the Open Phil report, check out these excerpts from Ed Yong's wonderful An Immense World:

We rarely distinguish between the raw act of sensing and the subjective experiences that ensue. But that’s not because such distinctions don’t exist.

Think about the evolutionary benefits and costs of pain [subjective suffering]. Evolution has pushed the nervous systems of insects toward minimalism and efficiency, cramming as much processing power as possible into small heads and bodies. Any extra mental ability – say, consciousness – requires more neurons, which would sap their already tight energy budget. They should pay that cost only if they reaped an important benefit. And what would they gain from pain?

The evolutionary benefit of nociception [sensing negative stimuli / bodily damage] is abundantly clear. It’s an alarm system that allows animals to detect things that might harm or kill them, and take steps to protect themselves. But the origin of pain, on top of that, is less obvious. What is the adaptive value of suffering? Why should nociception suck? Animals can learn to avoid dangers perfectly well without needing subjective experiences. After all, look at what robots can do.

Engineers have designed robots that can behave as if they're in pain, learn from negative experiences, or avoid artificial discomfort. These behaviors, when performed by animals, have an interpreted as indicators of pain. But robots can perform them without subjective experiences.

Insect nervous systems have evolved to pull off complex behaviors in the simplest possible ways, and robots show us how simple it is possible to be. If we can program them to accomplish all the adaptive actions that pain supposedly enables without also programming them with consciousness, then evolution – a far superior innovator that works over a much longer time frame – would surely have pushed minimalist insect brains in the same direction. For that reason, Adamo thinks it's unlikely that insects (or crustaceans) feel pain. ...

Insects often do alarming things that seem like they should be excruciating. Rather than limping, they'll carry on putting pressure on a crushed limb. Male praying mantises will continue mating with females that are devouring them. Caterpillars will continue munching on a leaf while parasitic wasp larvae eat them from the inside out. Cockroaches will cannibalize their own guts if given a chance.

Dr. Greger from 2005: Why Honey Is Vegan

Honey hurts more than just bees. It hurts egg-laying hens, crammed in battery cages so small they can’t spread their wings. It hurts mother pigs, languishing for months in steel crates so narrow they can’t turn around. And the billions of aquatic animals who, pulled from filthy aquaculture farms, suffocate to death. All because honey hurts our movement.

It’s happened to me over and over. Someone will ask me why I’m vegan—it could be a new friend, co-worker, distant family, or a complete stranger. I know I then have but a tiny window of opportunity to indelibly convey their first impression of veganism. I’m either going to open that window for that person, breezing in fresh ideas and sunlight, or slam it shut as the blinds fall. So I talk to them of mercy. Of the cats and dogs with whom they’ve shared their lives. Of birds with a half piece of paper’s worth of space in which to live and die. Of animals sometimes literally suffering to death. I used to eat meat too, I tell them. Lots of meat. And I never knew either.

Slowly but surely the horror dawns on them. You start to see them struggling internally. How can they pet their dog with one hand and stab a piece of pig with the other? They love animals, but they eat animals. Then, just when their conscience seems to be winning out, they learn that we don’t eat honey. And you can see the conflict drain away with an almost visible sigh. They finally think they understand what this whole “vegan” thing is all about. You’re not vegan because you’re trying to be kind or compassionate—you’re just crazy! They smile. They point. You almost had me going for a second, they chuckle. Whew, that was a close one. They almost had to seriously think about the issues. They may have just been considering boycotting eggs, arguably the most concentrated form of animal cruelty, and then the thought hits them that you’re standing up for insect rights. Maybe they imagine us putting out little thimble-sized bowls of food for the cockroaches every night.

I’m afraid that our public avoidance of honey is hurting us as a movement. A certain number of bees are undeniably killed by honey production, but far more insects are killed, for example, in sugar production. And if we really cared about bugs we would never again eat anything either at home or in a restaurant that wasn’t strictly organically grown—after all, killing bugs is what pesticides do best. And organic production uses pesticides too (albeit “natural”). Researchers measure up to approximately 10,000 bugs per square foot of soil—that’s over 400 million per acre, 250 trillion per square mile. Even “veganically” grown produce involves the deaths of countless bugs in lost habitat, tilling, harvesting and transportation. We probably kill more bugs driving to the grocery store to get some honey-sweetened product than are killed in the product’s production.

Our position on honey therefore just doesn’t make any sense, and I think the general population knows this on an intuitive level. Veganism for them, then, becomes more about some quasi-religious personal purity, rather than about stopping animal abuse. No wonder veganism can seem nonsensical to the average person. We have this kind of magical thinking; we feel good about ourselves as if we’re actually helping the animals obsessing about where some trace ingredient comes from, when in fact it may have the opposite effect. We may be hurting animals by making veganism seem more like petty dogmatic self-flagellation.

In my eyes, if we choose to avoid honey, fine. Let’s just not make a huge production of it and force everybody to do the same if they want to join the club.